SURVIVAL RESEARCH LABS

By Isabelle Kohn

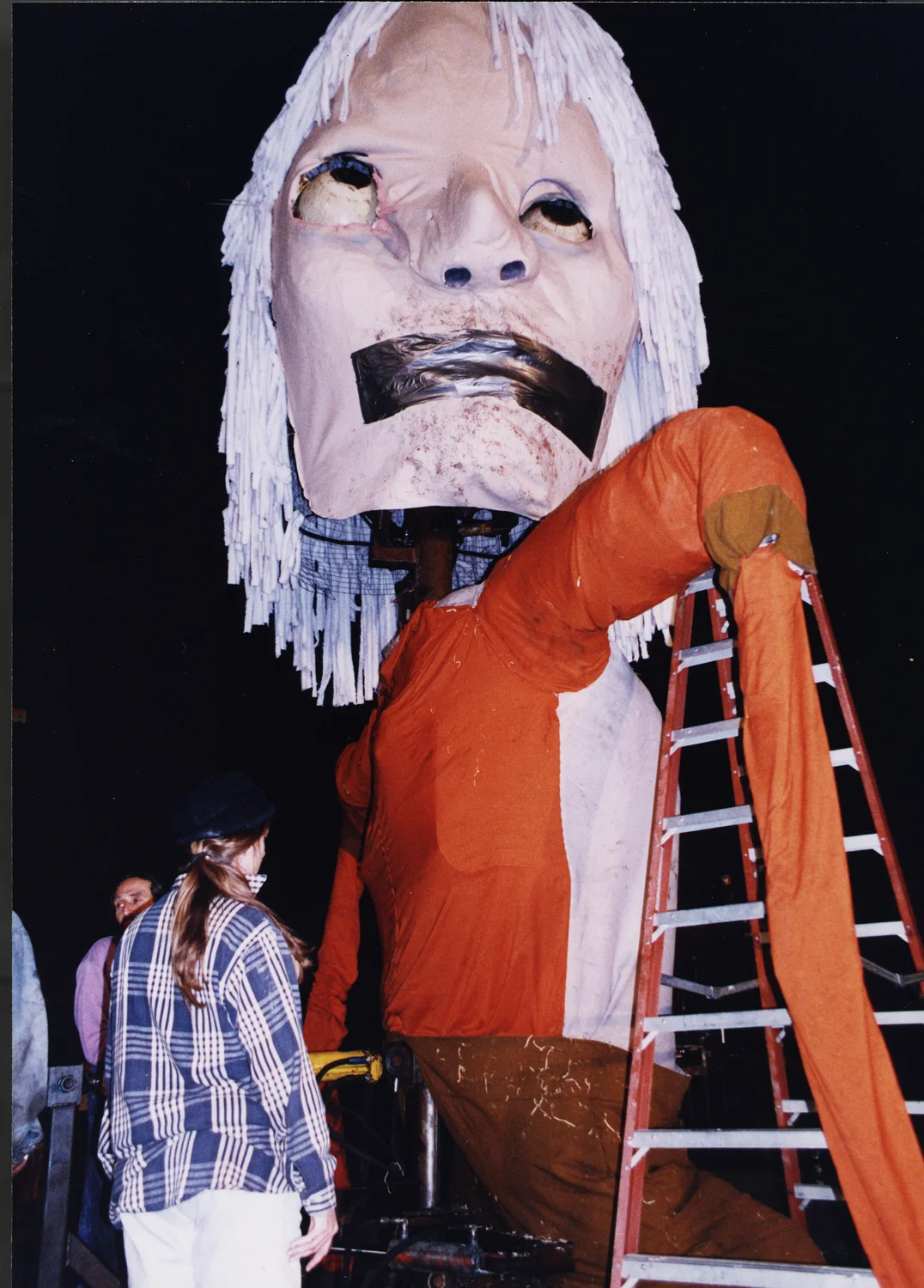

Photos Courtesy SRL Archive and Mark Pauline

Mark Pauline has spent the last 37 years making machines that remind you that you’re going to die. From his Northern California laboratory he raises hulking, screeching monstrosities up from the dead and sends them not to the assembly line but to the limelight. Mark doesn't make practical robots, he decided very early on in his life that he never wanted to make any machine that would make anything that would make anyone money or hurt anyone. No construction. Instead he makes feral creations hell-bent on destruction, multi-ton insults to logic predestined to become actors in a glorious apocalypse party. Operating under his nom de plume 'Survival Research Laboratories' Mark builds his robots to fight each other to the death in lurid, sonically devastating acts of ultraviolent performance art. When you see an SRL show, you either see God or the insides of your eyelids.

“For someone looking for a good time, I don’t recommend it.”

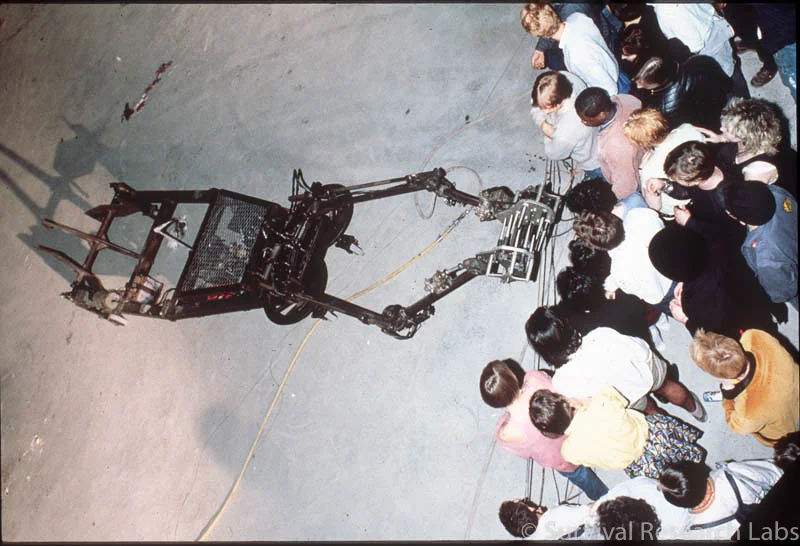

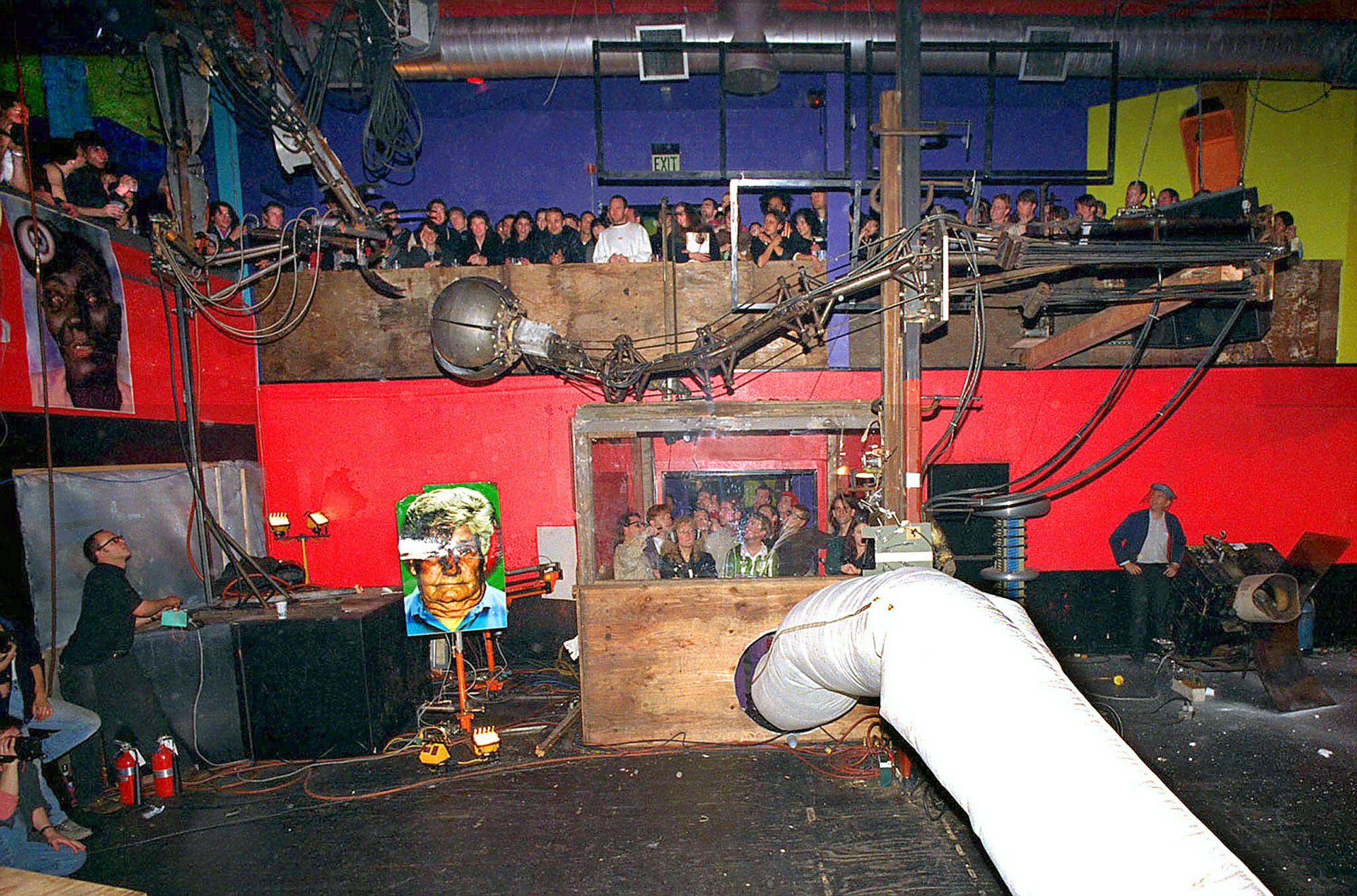

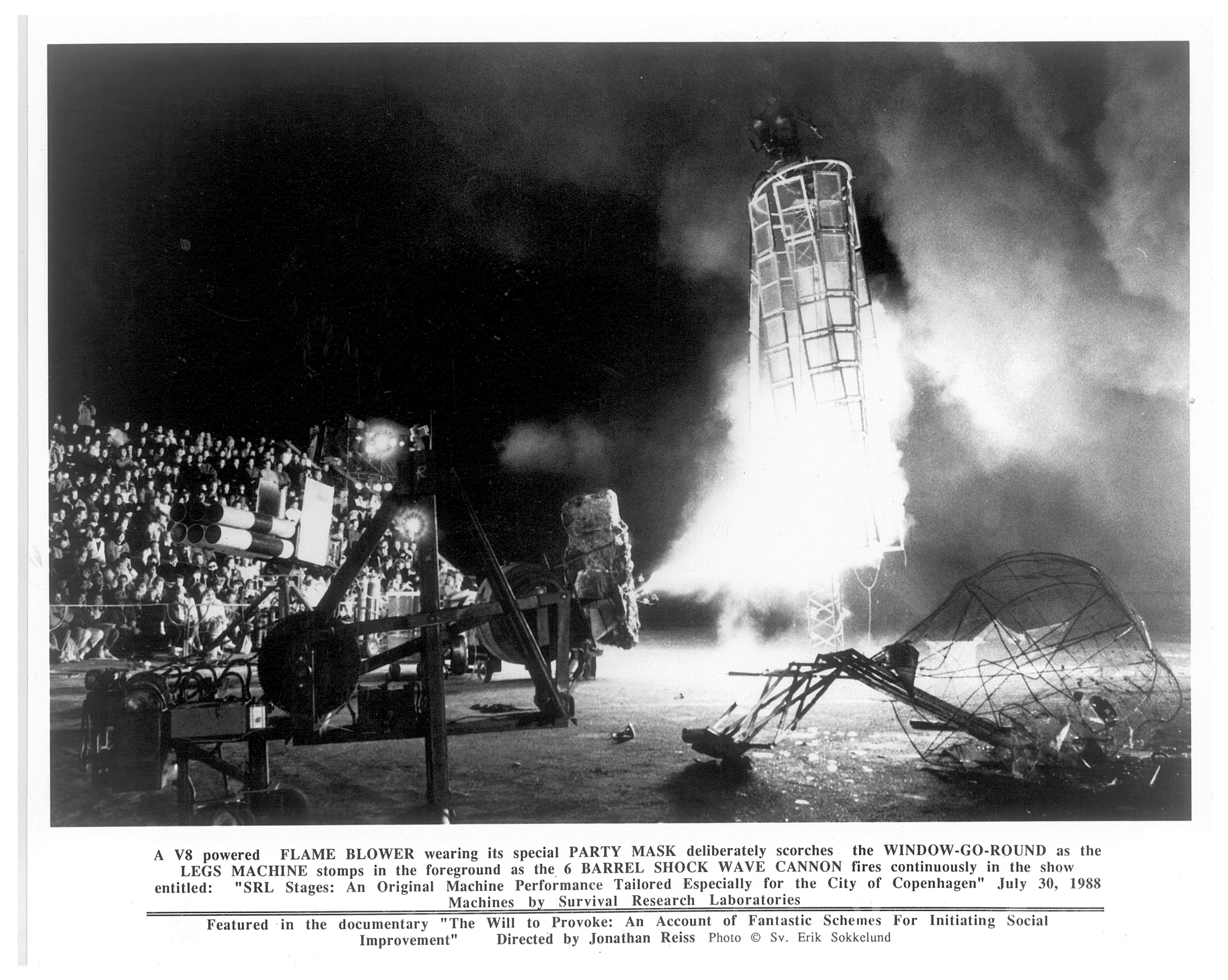

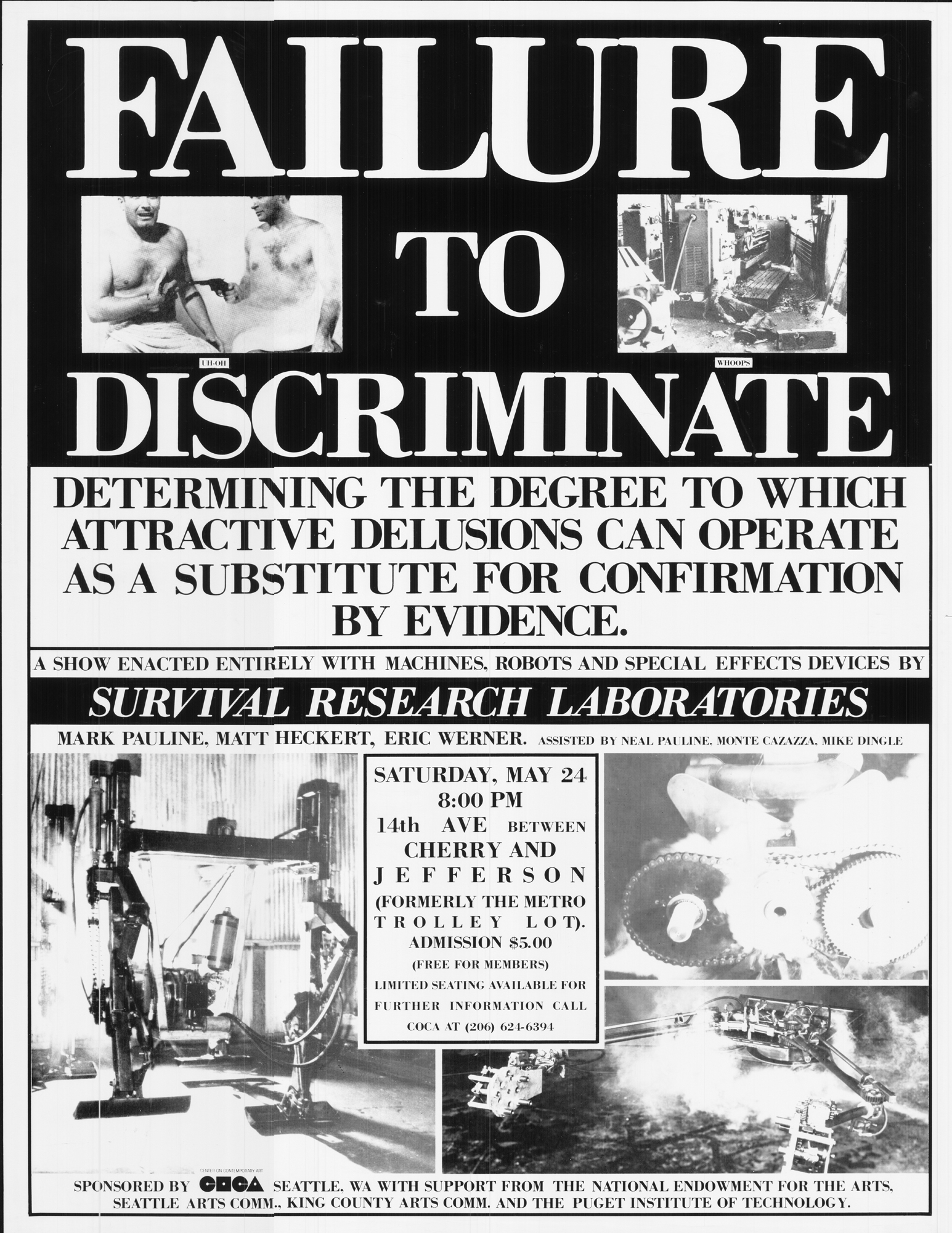

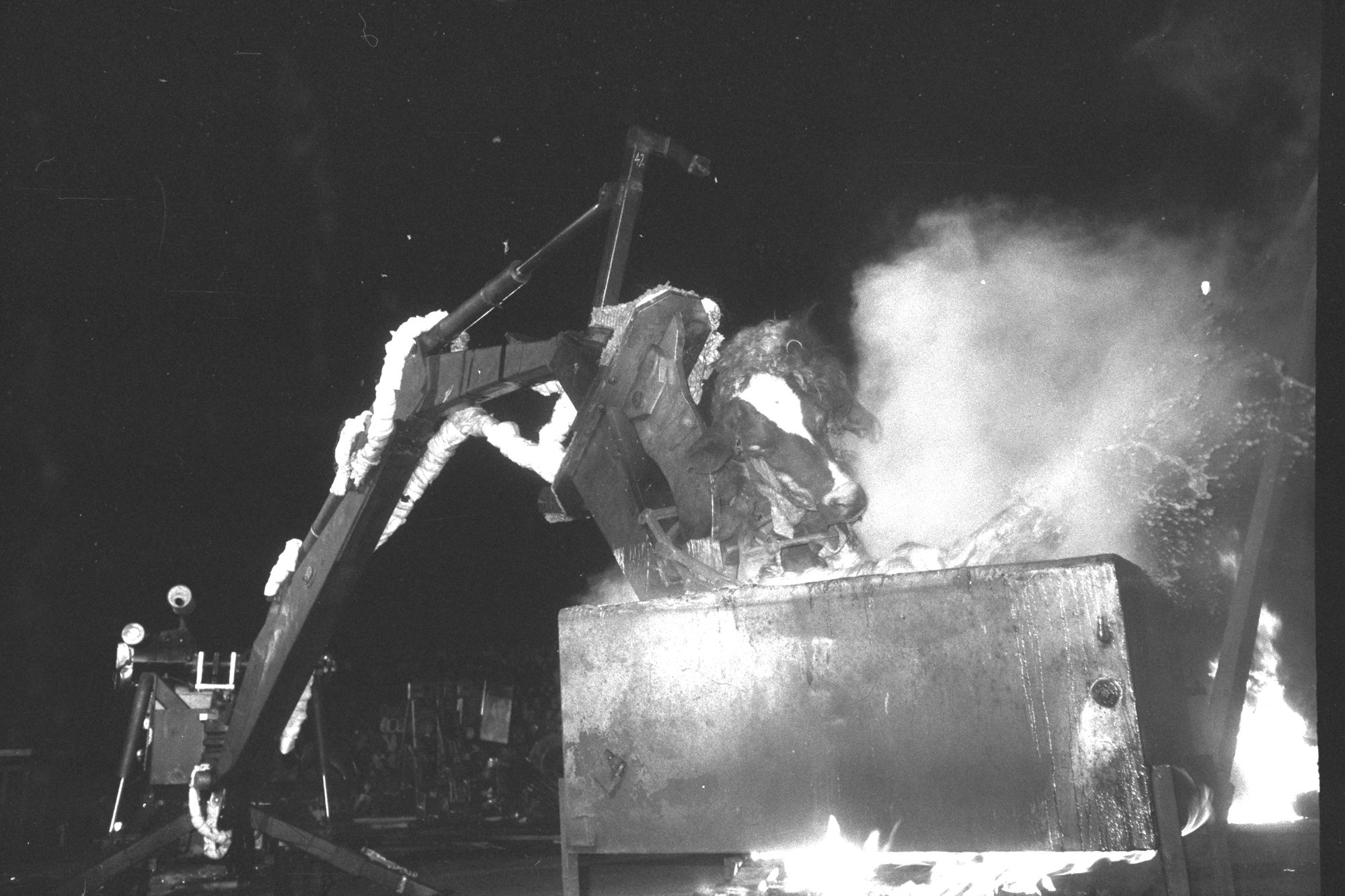

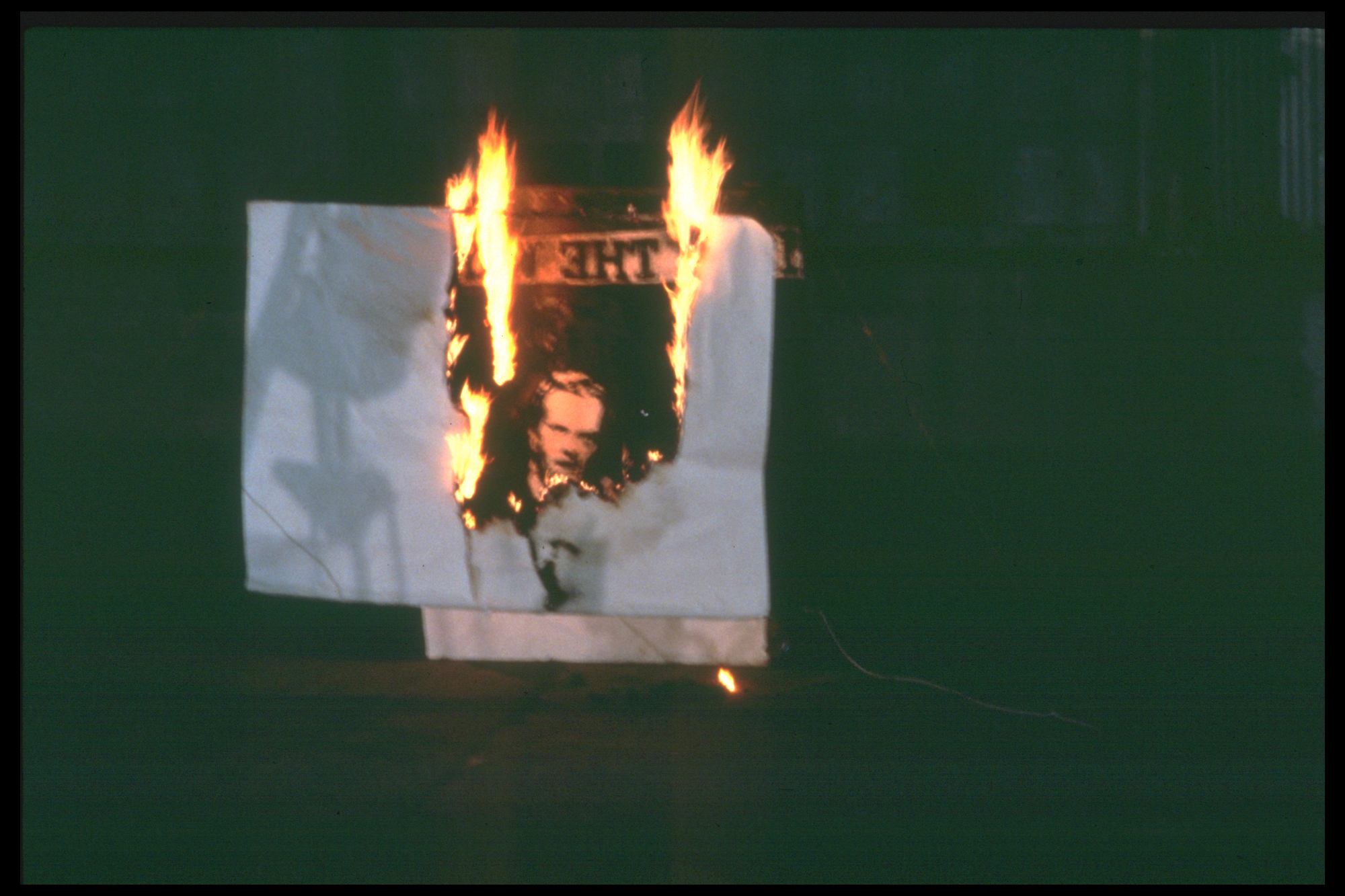

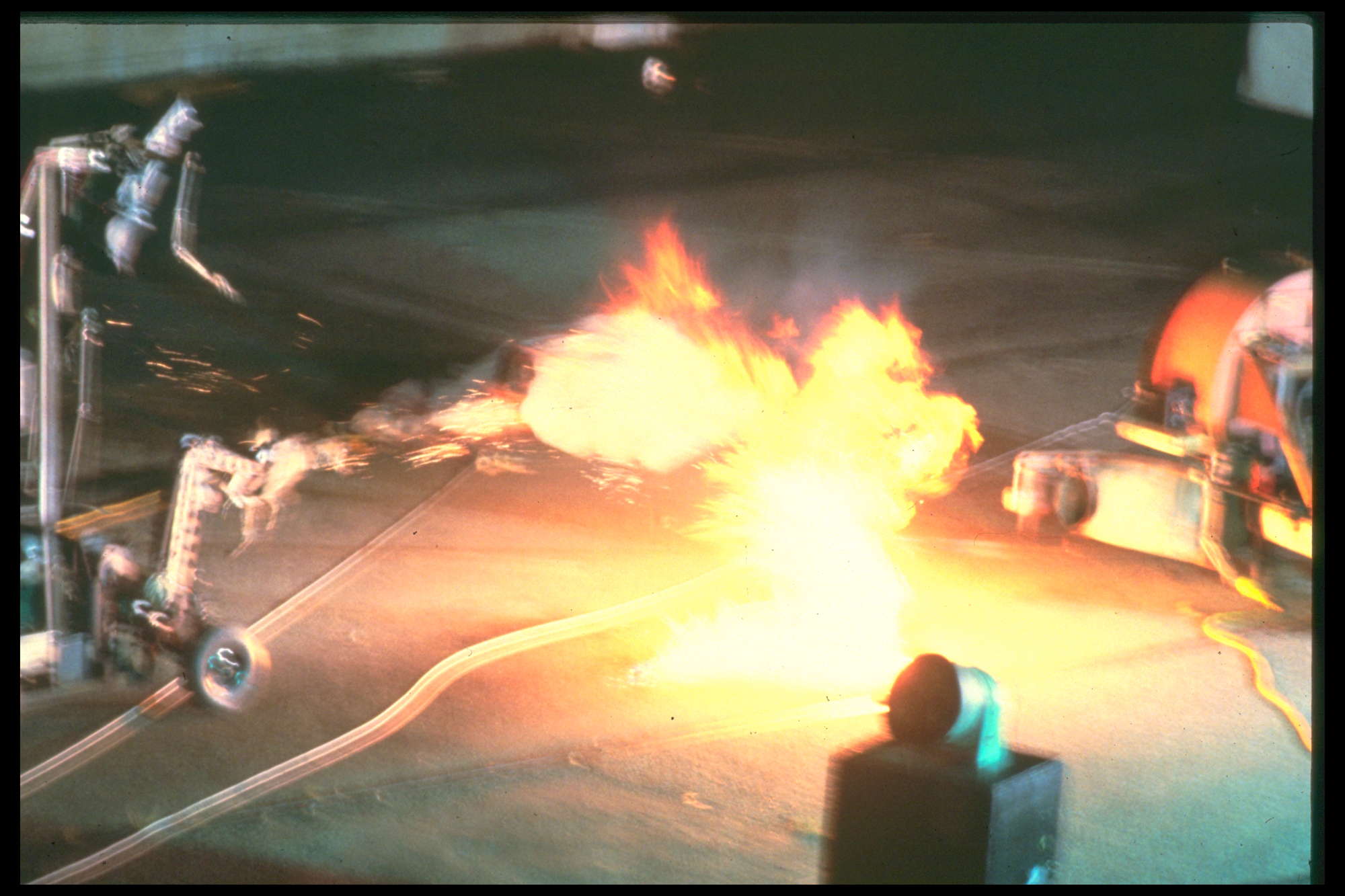

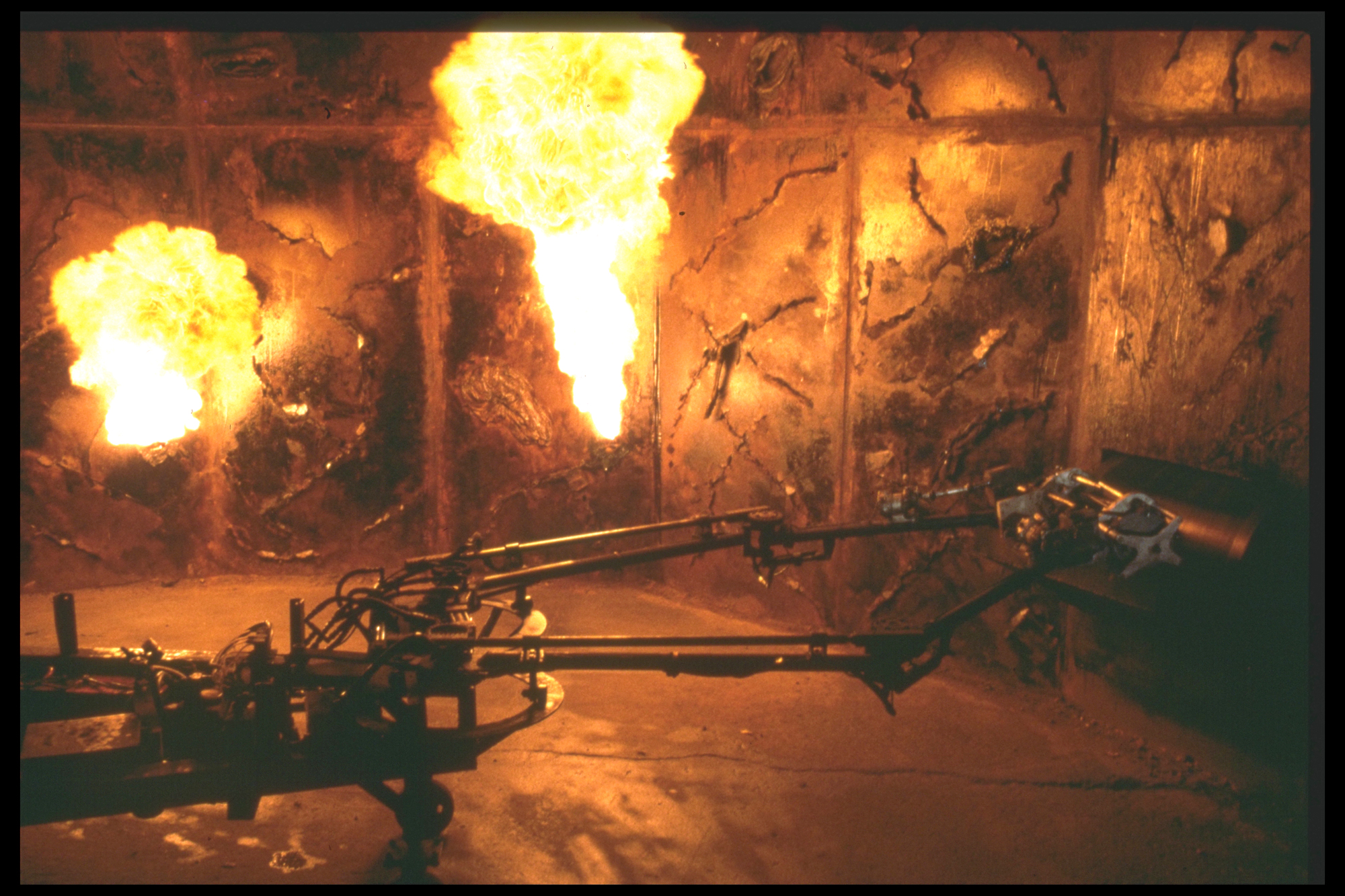

Mark's machines are a delivery method for fear and if you’ve ever enjoyed Bosch, Gotterdammerung or Mad Max, the scale and ferocity of his performances might resonate with you. SRL shows are like whatever you think hell is: fiery explosions licking at your face; the penny taste of fear; erratic and insanely, painfully loud noises; all emanating from a small army of pilotless animatronic robots locked in a ceaseless ultraviolent melee. It is sadism in the WASP-y face of normalcy. Crowds in obvious physiological distress stand behind barricades looking one of two ways: terrified and praying that the carnage will end before their eardrums implode or calcified in maniacal catatonia, eyes wide and teeth bared in a slick grim reaper smirk as though Jesus himself has swooped down and delivered a message of war so close to their faces they could smell his reeking thousand year old breath. Audience members become involuntary participants. Glass is shattered. Metal is rent. There are smoking craters. There are ruins. At one show in 1995 a full size remote controlled car jousted around wielding a 15' tall spinning cone of school desks, legs pointing outward, a naked baby doll impaled on the end of each sharpened desk foot. "It's as if several junkyards' worth of our refuse had risen up to let out an immense collective scream," wrote The Boston Globe’s Leighton Klein of the shows, over 50 thus far from San Francisco to Copenhagen to Tokyo. “For someone looking for a good time, I don’t recommend it.”

Why is any of this attractive? Because fear. Fear is therapeutic. “Destruction is the ultimate power of the universe. Being destructive is the closest a human can get to being a god. Creation is a distant second in that regard. My ultimate fantasy about what people should take away from these shows is that when someone who’s been to a show is on their deathbed, the images from an SRL show are some of the last things that are crossing the path of their mind before they expire."

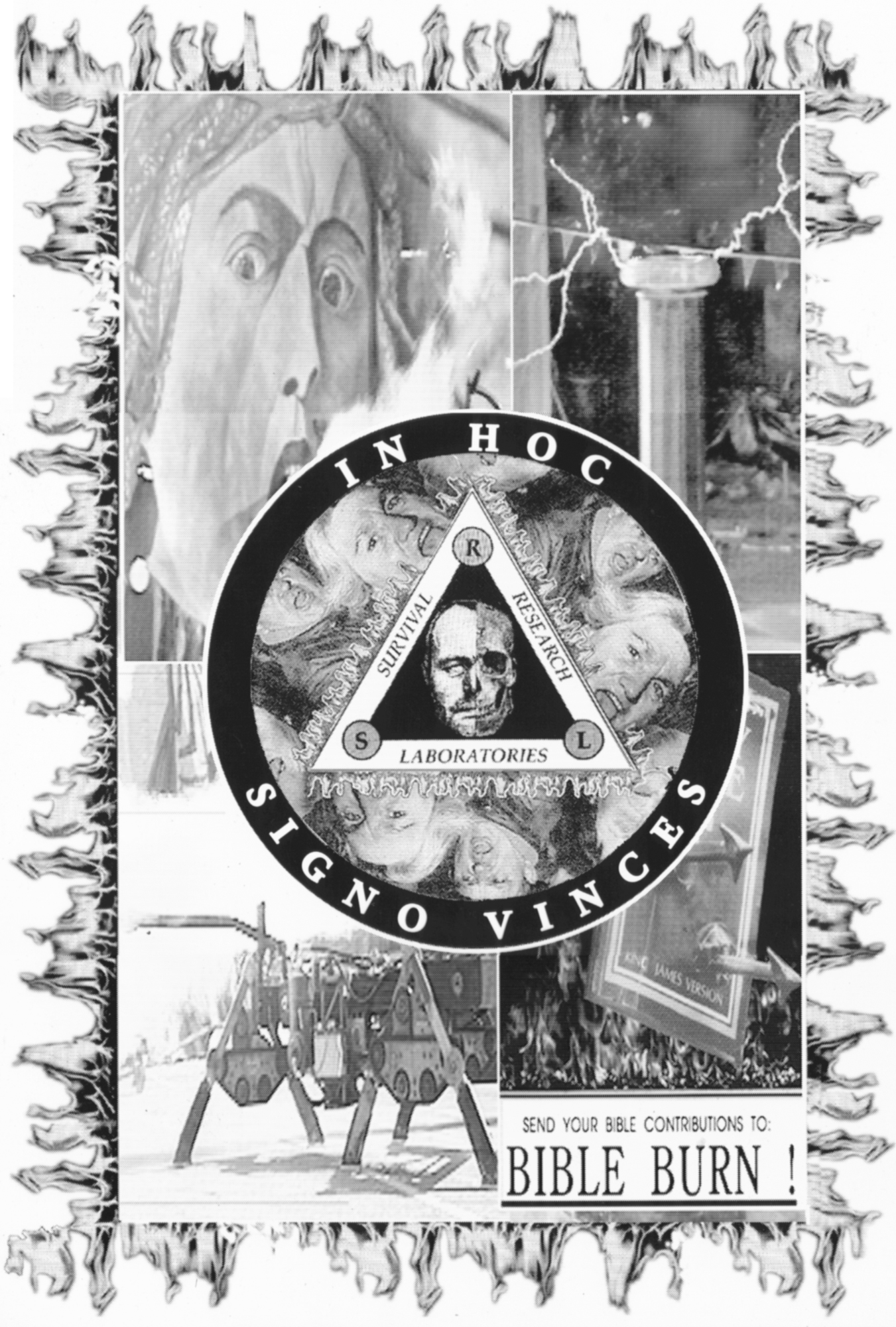

And in the art world, Mark is … not part of the art world. What he does has no highbrow intention or inspiration, it is meant to make you shit yourself for his enjoyment. When I ask him whether he thinks his work is art, he says, “I don't need to think anything about it. I just need to do it.” Here’s the thing about Mark: it doesn’t matter if what he does is art or not, because he’s the only non-government contractor in the world who’s making machines on this scale. Regarding the decades of 16-hour days designing and assembling impractical machines, the battles with local authorities over fire safety and the constant grind for funds to produce his work Mark says it "seems like the only way.” Like any machine, a man has in him a calculable number of productive hours. So to spread his prodigious workload over to a few more people Mark created Survival Research Laboratories, the machine performance collective that’s been staging his disturbing productions since 1979.

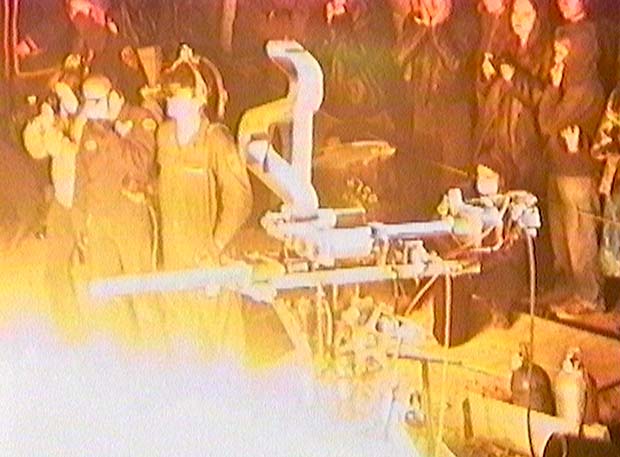

Staged shortly after the SF Fire Dept warned SRL never to perform in SF again. Good enough show that Mark Pauline and Mike Dingle got arrested and convicted of arson with the intent to injure the public! Edited by Alan Kelley. Video directed by Dave Scardina.

“People think I’m a maniac,” he says. “I act on my animal instincts like any other criminal, but I also act on my creative ones. That makes me more legitimate.”

"I build machines that have a lot of character," Mark says. Every time SRL does a show, he makes the ten o’clock news. “People think I’m a maniac,” he says. “I act on my animal instincts like any other criminal, but I also act on my creative ones. That makes me more legitimate.” At one show, called "A Fiery Presentation of a Dangerous and Disturbing Stunt Persona", he tested how far possible physical endangerment could go. Mark had his assistant, Matty Heckert, drive a go-cart through an exploding gasoline trough. “We used the audience not so much as performers, but as targets threatened with destruction! Yeah! Matty had this flamethrower he kept on shooting toward the audience, and I had my radio control car [a seven hundred pound life-size car that’s run by radio control with no driver], with a giant buzz saw attached to the front of it, go berserk. I made it careen completely out of control, break through the Plexiglas protection barrier and run out into the audience, knocking people over!"

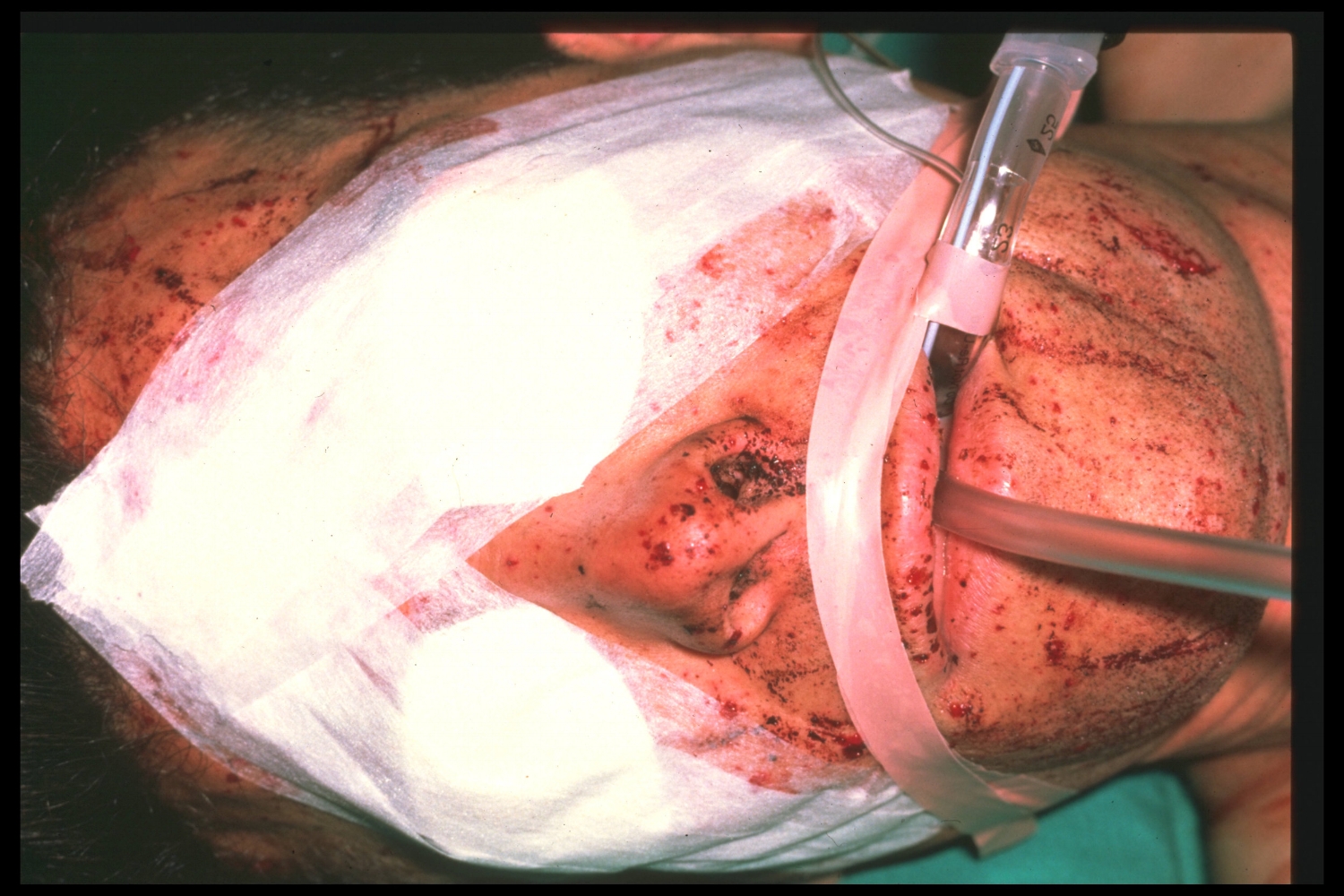

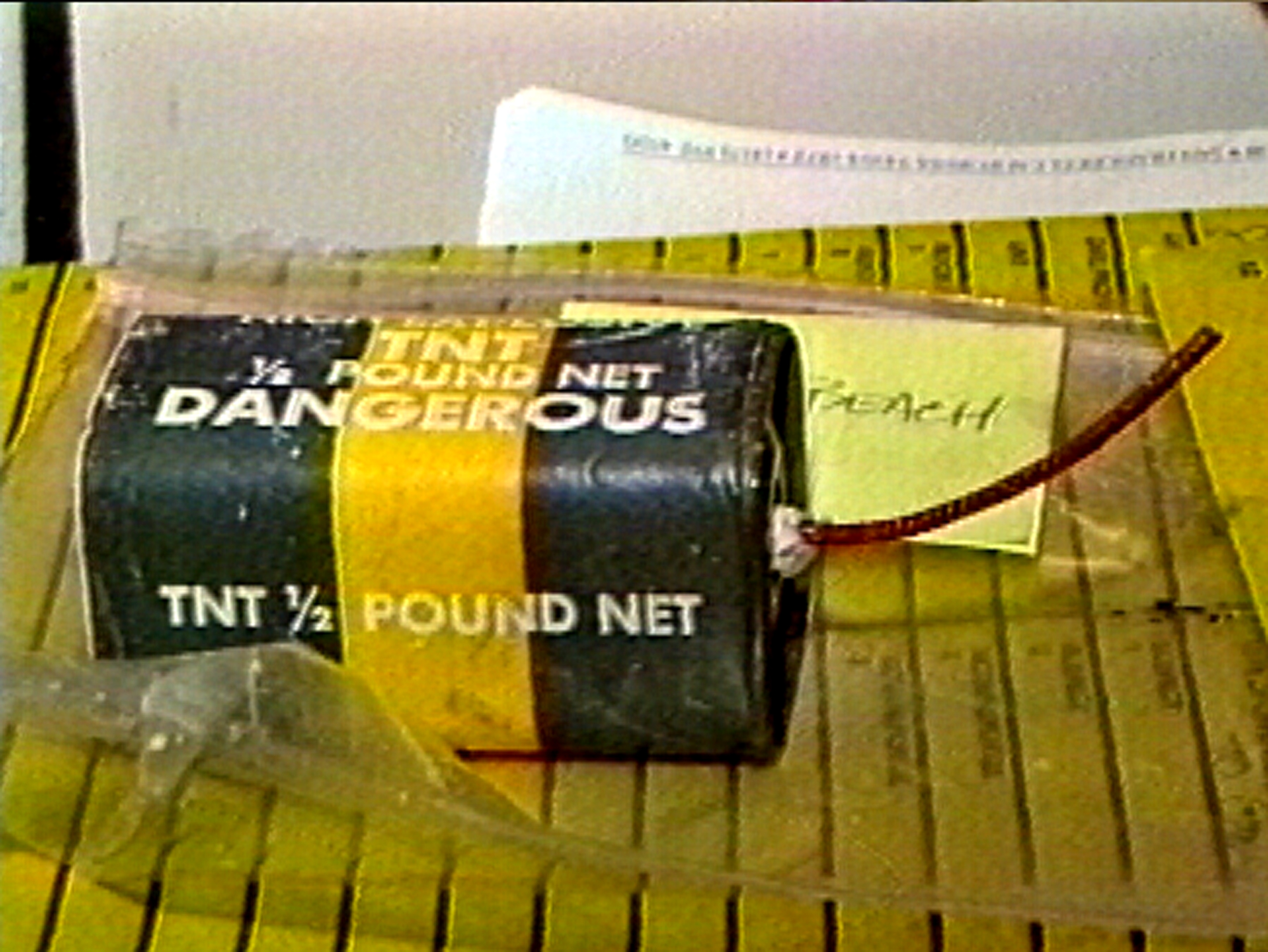

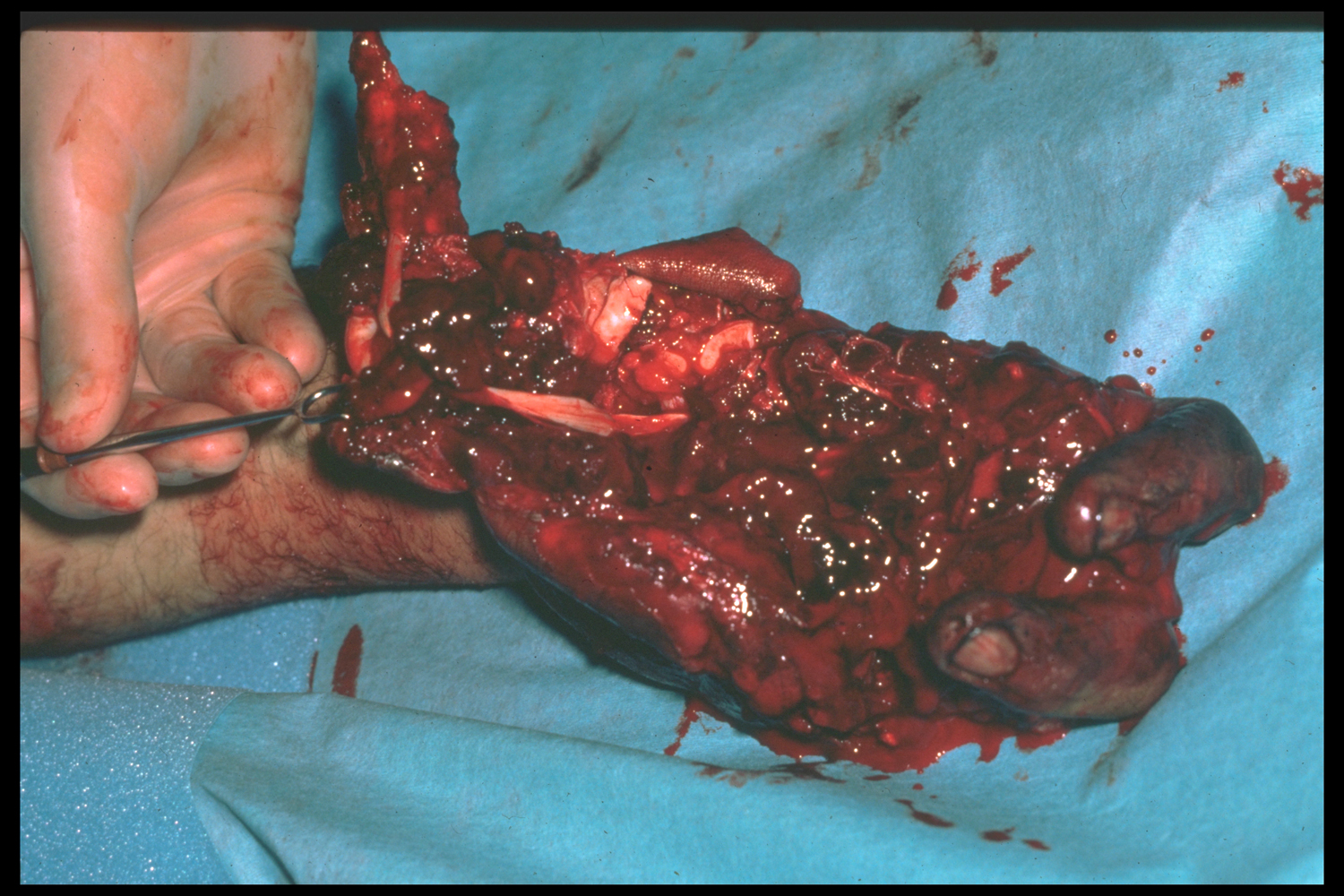

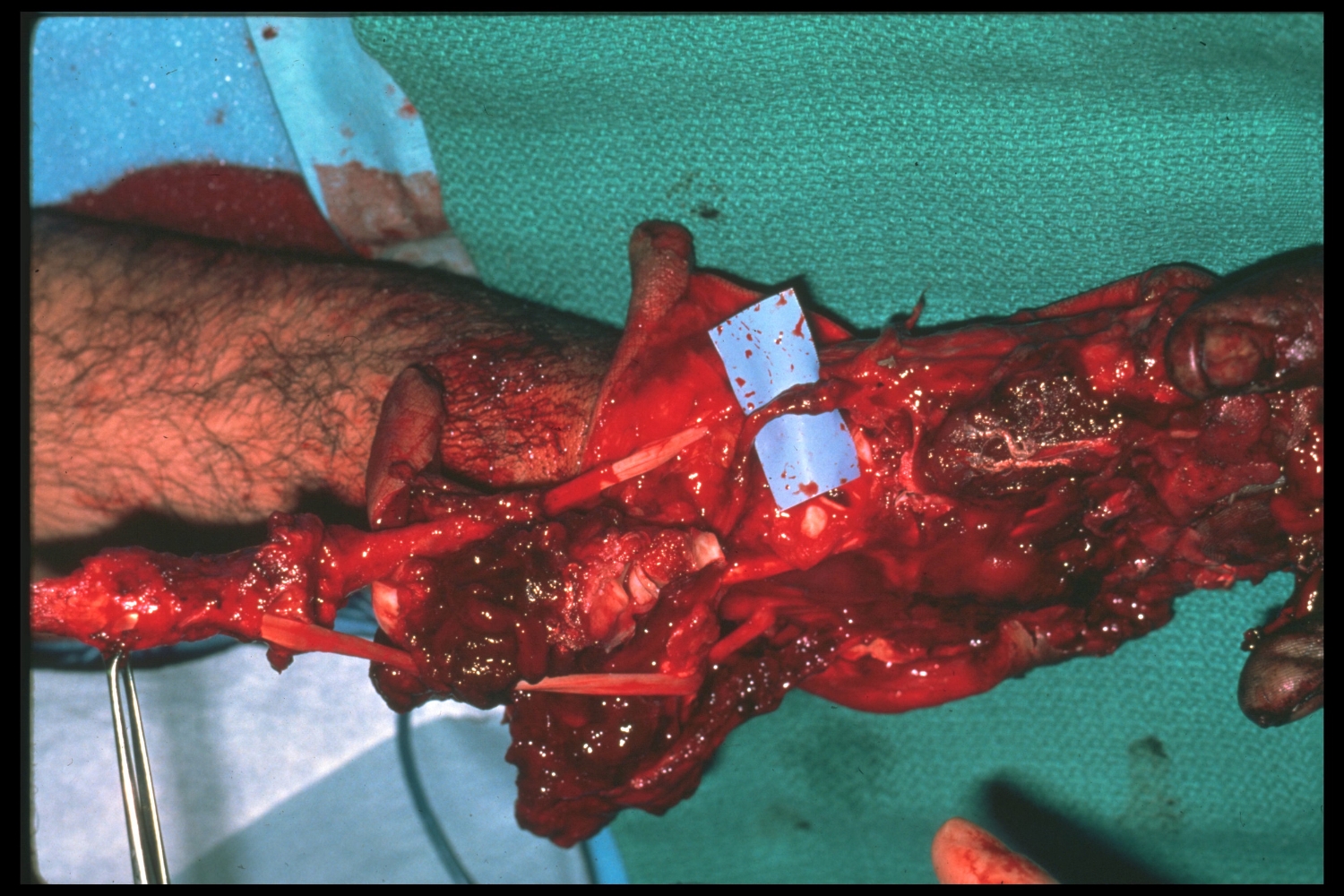

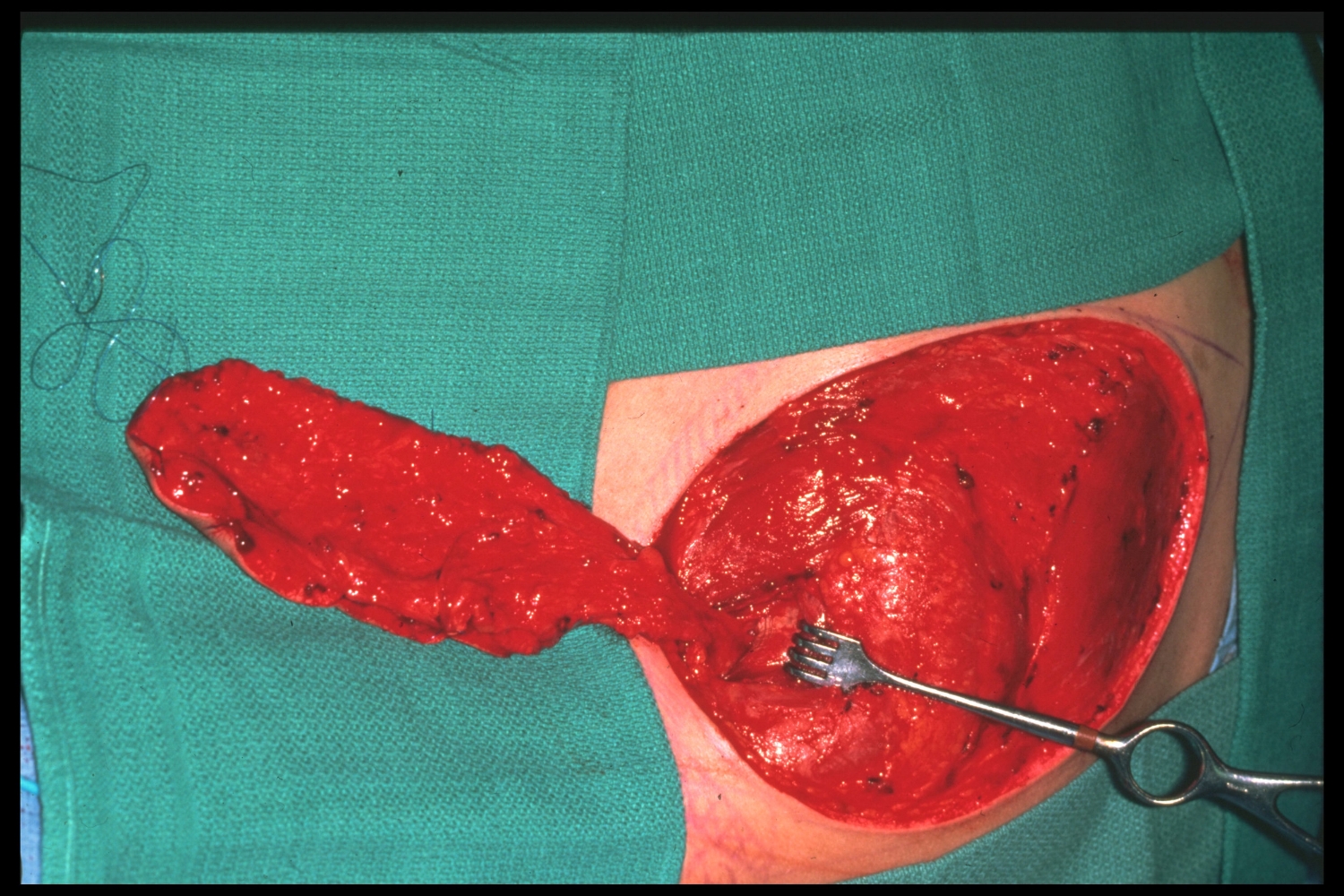

Machines are much more powerful and dangerous than any human and when they interact violently it creates an impression too deep to forget. Mark has his own indelible impression from his machines, 1982 he was working with a rocket motor that exploded in front of him deleting all but his middle finger from his right hand. He was rushed to the hospital where his hand was 'repaired' by taking a couple toes and some skin off his back to compile what he now calls his 'gimp hand'. "I don't know what's wrong with a gimp hand." Mark declares, "You could take over the world with a gimp hand if you weren't so fucking lazy."

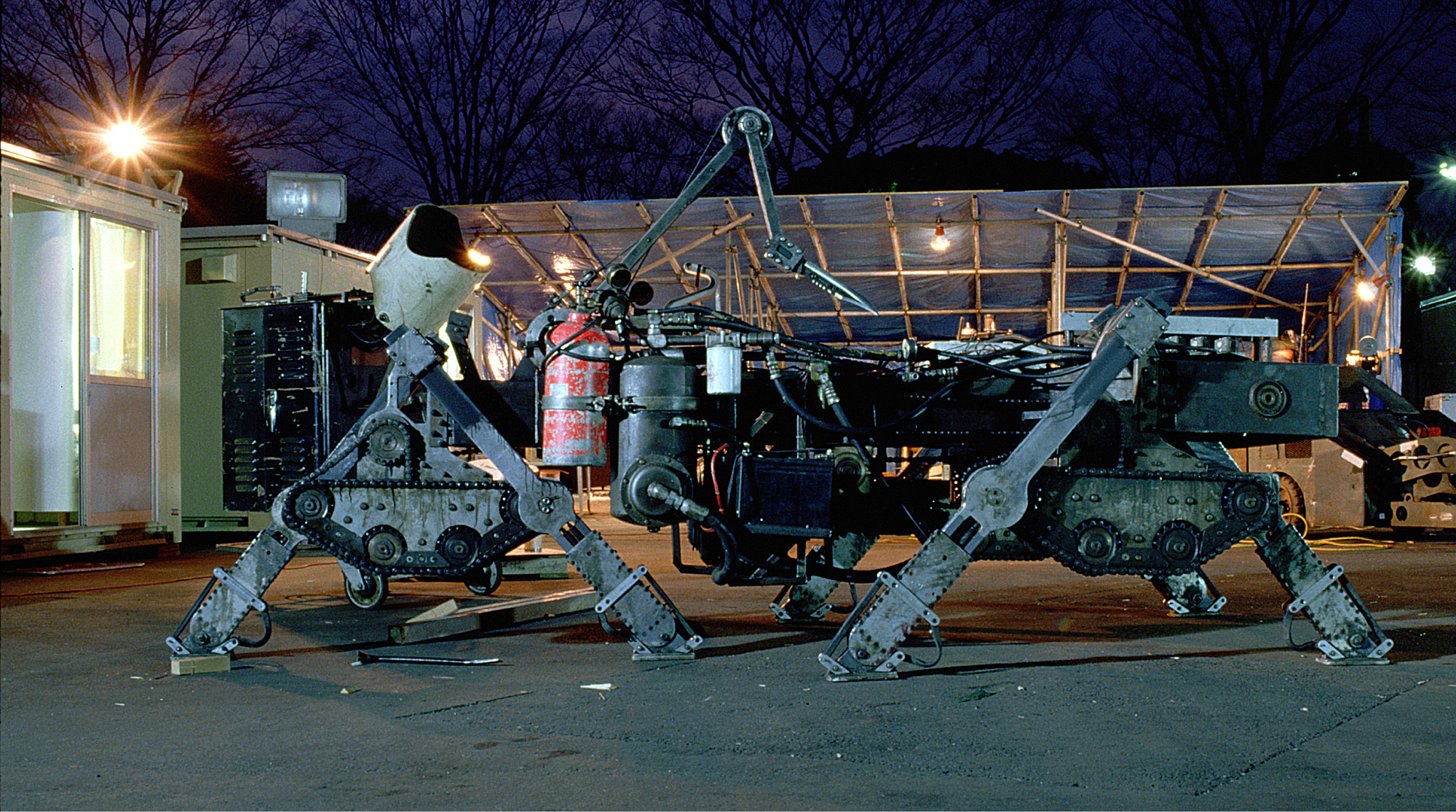

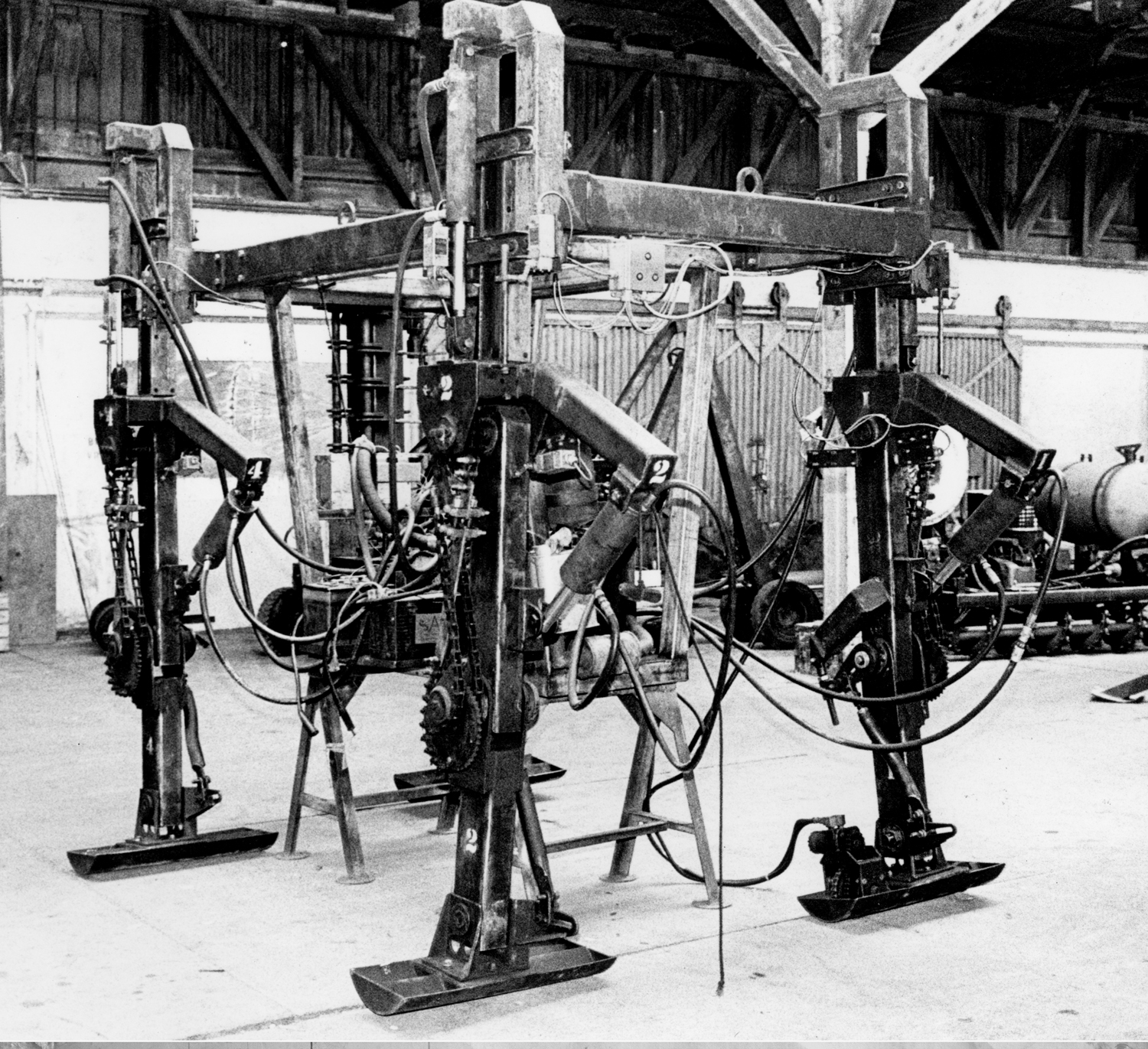

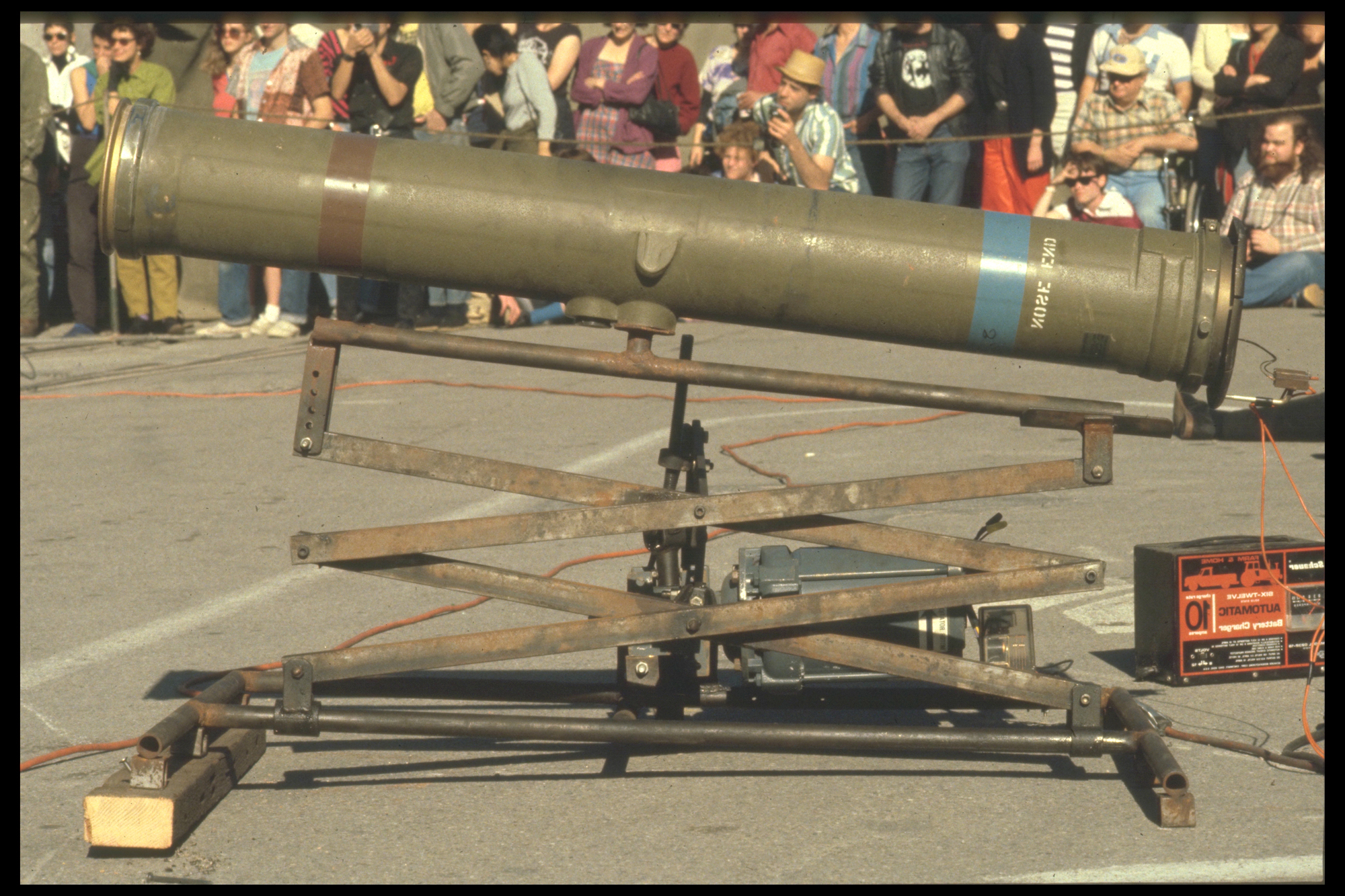

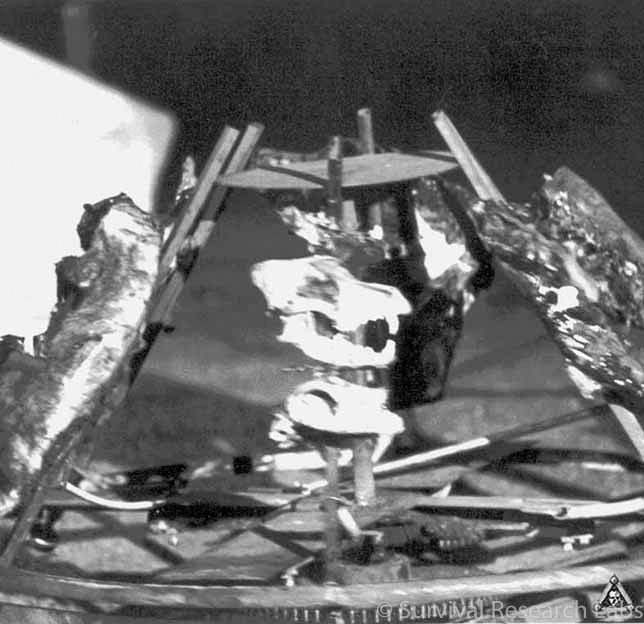

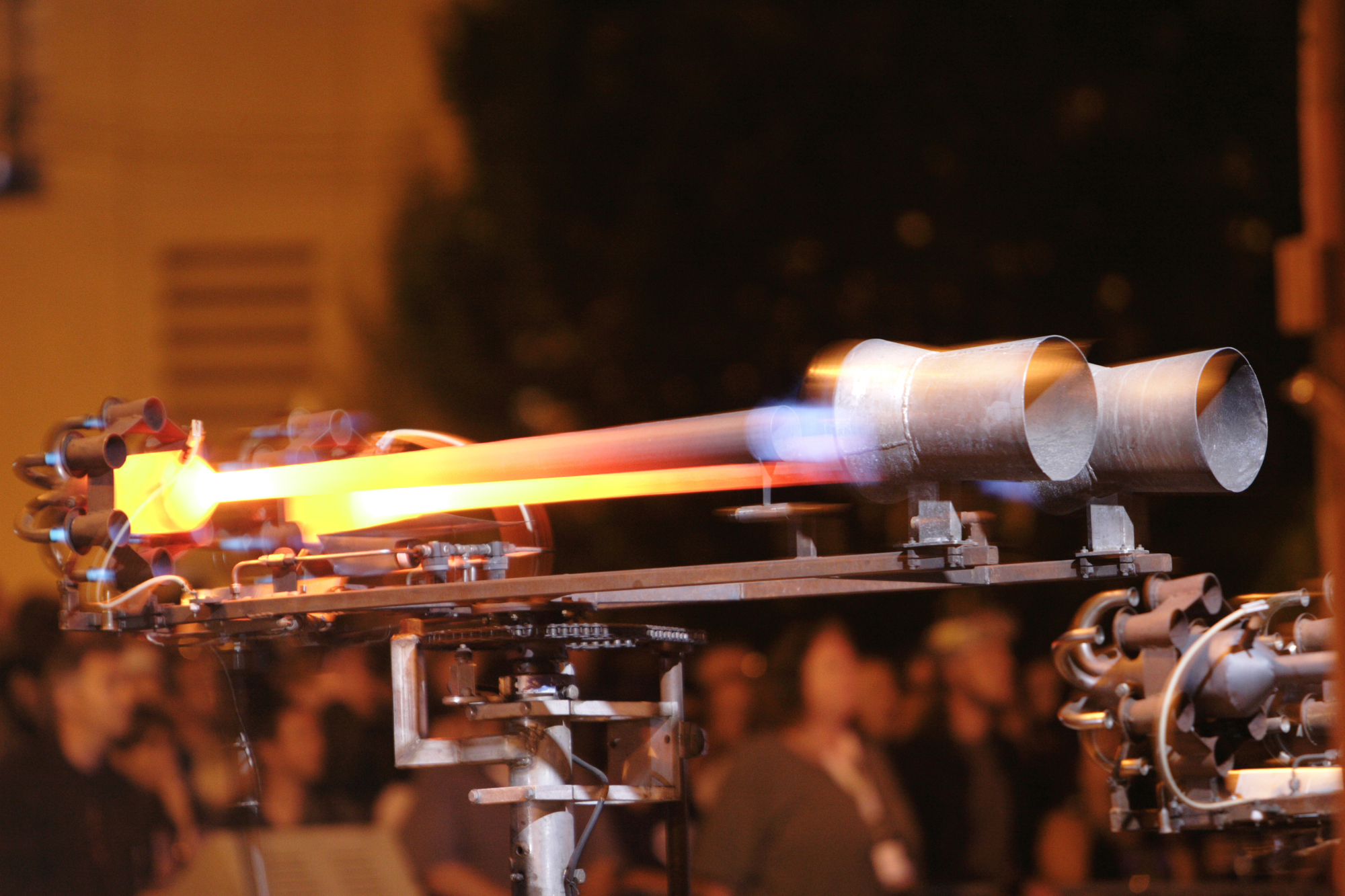

But as cute as a gimp hand may be, what’s most endearing about Mark is the sense of responsibility he feels to liberate machines from banality. Everywhere he looks he sees mega-ton pieces of steel crushed under the weight of their own unused potential, bored by their routines. He digs deep into the core of their personalities to discover what they really want to be, cultivating their idiosyncrasies like a Montessori Dad. A mass of cable and tubing becomes the Hand-O-God, a great and terrible metal appendage whose wrath strikes with eight tons of force. The wheels and 500 cubic inch engine of a Ford El Dorado become the ultra-dangerous Pitching Machine, capable of hurling six-foot long, two by four boards 120mph at a rate of two per second, fast enough to pierce walls hundreds of feet away. Airplane jets become a pillar of fire called the Flame Hurricane, five LOUD 150 LB thrust Pulsejet engines and a system of 8 by 8 foot louvers arranged in a 45 ft. circle to produce a rapidly rotating column of hot, high velocity hurricane like wind. Gasoline is injected into this swirling vortex of hot air at a pressure of 1000 psi and a flow of 1.5 gallons per second, producing a flaming layer on the exterior of the rotating air column. Powerful fuel vapor explosions are a distinct possibility.

So, what do we do? We go to see him, and by we I mean myself and the 46-year old man who will be documenting the experience on celluloid. Perhaps we too will become targets threatened with destruction, so we bring half a dozen fresh donuts just in case.

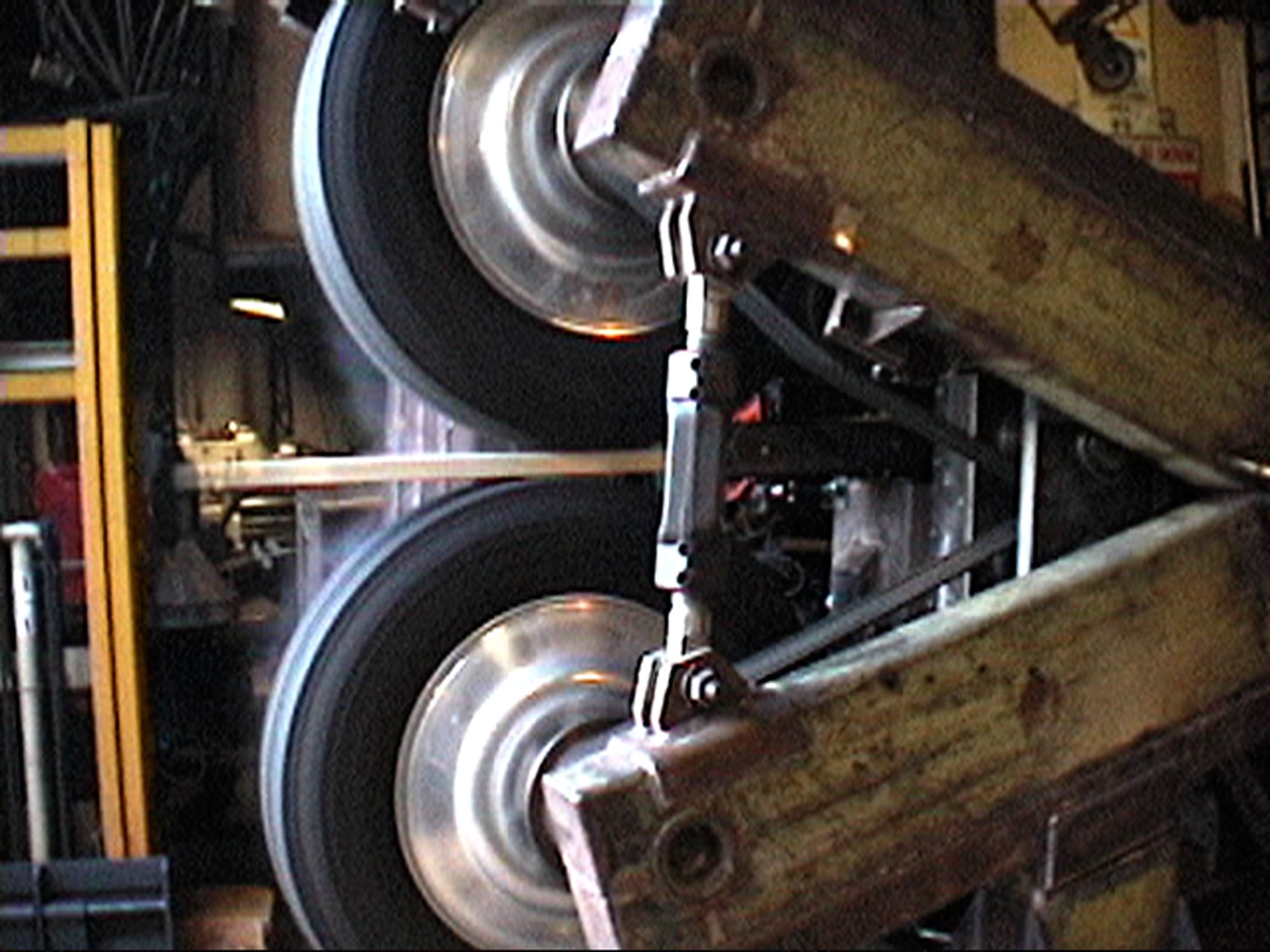

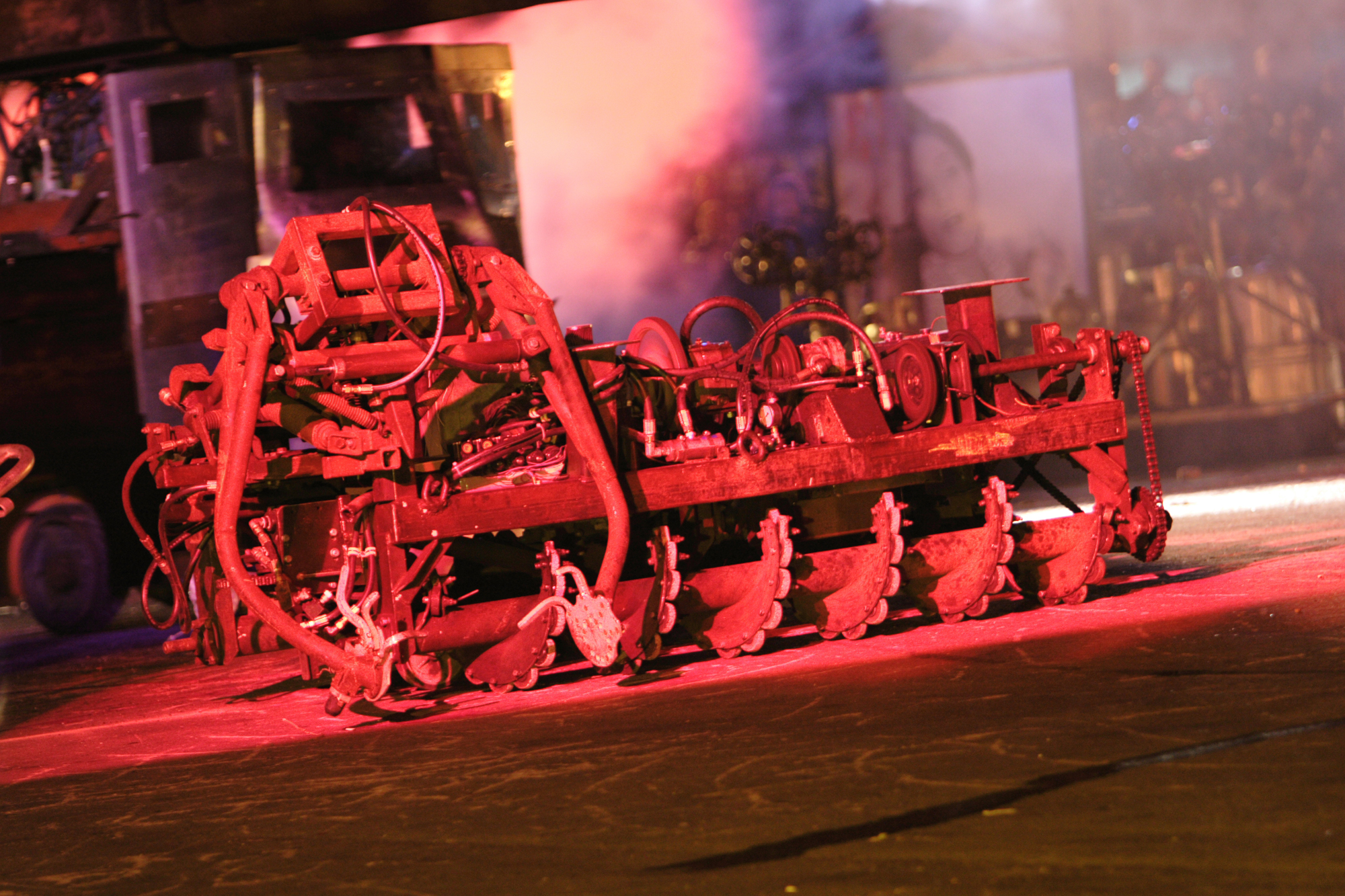

When you enter the 20,000 sq. ft. warehouse that is Survival Research Laboratories' home, you enter a shrine to potential. From every corner, piled high to the dusty rafters, are dead metals waiting to be reborn; several full hardware stores and an enormous junkyard's worth of parts, pieces, shapes and scraps on one side of the building and an a full array of high to low tech forming and shaping tools and machines on the other. Amongst it all is Mark, who we find fiddling with the Track Robot, an SRL machine from the old days that he outfitted with some sort of groundbreaking virtual reality setup two nights ago. It’s casual. He’s joined by his son, Jake Eddie, who would definitely be a finalist in the World’s Most Endearing Spawn competition if such a thing existed, mostly due to his capacity to pester Mark to no end. Mark accepts our donut offering with his gimp hand and doesn't immediately try to kill us. So far so good.

We get right into it. Like his robots, Mark is steely and direct, almost forcefully so. “I do not see myself in any of these machines,” he says when I ask him if the personalities he brings out of them means they have a soul. “They're strictly externalized phenomenon. I think what they are, is an extension of my attitude. They're kind of like a stance, you know? Like posers. I pose them in the same way people pose dolls. Then, to be able to have a machine show work the way you intend it to, you've got to have a backdrop of some kind. It could be a fabricated backdrop; it could be a location that's just amazing. We did a show in a giant toilet paper factory from the 30s in Austria one time. Our machines just smashed holes in the concrete wall and we put the bleachers on the other side of these holes.” A good show needs a good name, SRL's of the past have been titled "An Explosion of Ungovernable Rage", "Ghostly Scenes of Infernal Desecration", "Further Explorations in Lethal Experimentation" and "A Calculated Forecast of Ultimate Doom: Sickening Episodes of Widespread Devastation Accompanied by Sensations of Pleasurable Excitement", you get the idea.

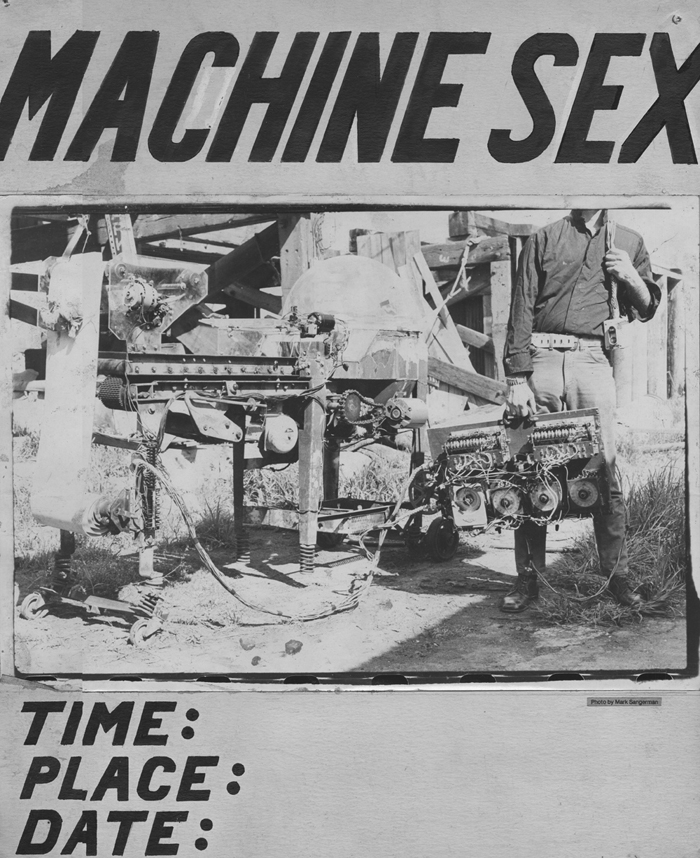

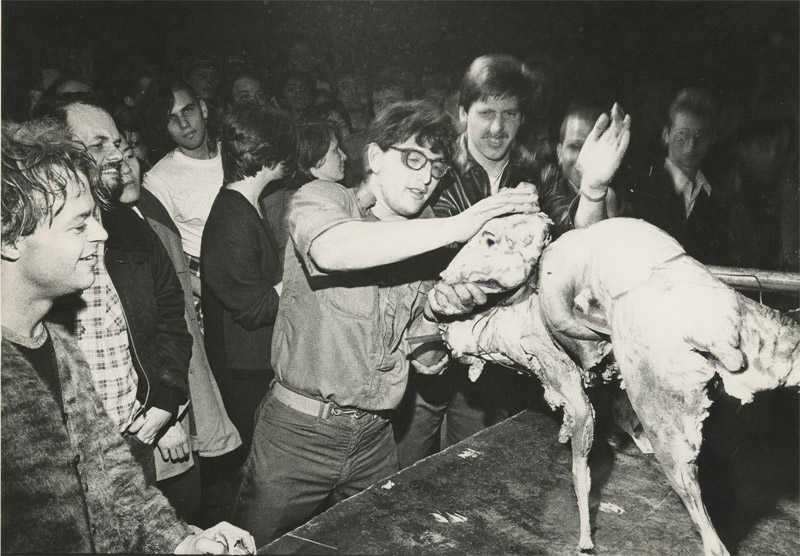

The first SRL show, “Machine Sex,” opened Sunday, February 25, 1979 at Alex’s Service Station in the North Beach district of San Francisco. Pauline didn’t bother asking permission from eponymous Alex, or from anyone. A crowd of about 30 gathered as he unloaded the De-Manufacturing Machine, the first ever SRL creation. He’d liberated its components from a brewery, suturing a conveyor belt to a high-speed fan topped with a Plexiglas bubble. Anything conveyed into the spinning blades would be "de-manufactured" to pieces, briefly whirling up and around the transparent dome before falling back to earth. The remnants collected on a platform below before being ejected violently out of the machine. Tinny PA speakers played a slowed down, tape-distorted version of The Cure’s "Killing an Arab" at an uncomfortable volume. The De-Manufacturing Machine spun to life. One by one, eight dead pigeons journeyed down the conveyor belt. Pauline had killed them himself, using his slingshot in an abandoned warehouse; he’d also dressed them in Arab doll costumes. It was 1979, and in the American imagination the traditional white robes evoked the Shah of Iran, OPEC, and the energy crisis. The octet of dead, costumed poultry proceeded into the blades, transmogrified into a pulp of flesh, blood, and cloth that the De-Manufacturing Machine then spat at the audience. After Machine Sex, he did a piece called Assured Destructive Capability, where he used a machine called The Stabber to mutilate a teddy bear wearing a mask of Leonid Brezhnev. At some point, there was a tree laden with cat corpses. From there, it only gets worse.

“I basically consider myself to be a comedian. These are just gags. It's like all a joke ultimately. I mean, to me, I do it because I think it's funny. I think it's funny to do these shows and I always like to pretend there's a reason for it but really I do it because I think it's funny more than anything else.” So SRL is like a decades-long prank, one executed with an unfathomable degree of meticulousness and precision? But a prank on whom? People take in Mark’s work in the same way they take in religious sacrament or ayahuasca-soaked spirit realizations. Despite his urging of “Please, don't anybody look to SRL shows for guidance in the real world,” people search for meaning in it, but SRL doesn't hold the same kind of answers as the rest of art world. Mark’s work is not subjective. It either changes you or you’re just deaf. This shit will level you and everyone else on the same playing field.

Back at SRL, Mark fires up the Spine Robot. For the uninitiated, the Spine Robot is a tree-sized metal snake attached to what I think is the liberated remains of a tractor but may also be a repurposed elevator. Its head is a 400-pound, razor sharp claw which moves at 20 feet per second. Its neck is 15 feet tall, reptilian, and comprised of hundreds of discs that act like immortal vertebra. Its heart is a fuel-injected 37 HP industrial motor. It’ll lift up 28,000 pounds before it breaks. That’s what it was made for, to lift and fling impossibly unwieldy objects that aren’t made for flight.

And that’s what I’m up against as I stand just out of reach of a Spine Robot death grip. Mark turns it on. He nudges some controls. It breaches the boundaries of animation as electricity pulses life force through its nuts, pun totally intended. Mark presses a switch that makes the neck coil up like a python ready to eviscerate you. That function was premeditated, no doubt. Like all of Marks machines, the Spine Robot is half theatrical, half pragmatic. As its vertebrae swings its head around, twisting with the flexibility of a building-sized serpent, I kind of felt like I had to shit. At no time was I in this thing’s way, nor did Mark try to fuck with me from behind the controls, but even from the safety of where I stood something about it made my adrenal glands squirt hot emergency juice and my heart pound with inefficient rapidity. There’s no denying it Mark's machines devolve you into a logic-defying brainstem screaming 'FEARFEARFEAR', stuck between fight-and-flight. “People have this sort of natural, weird, instinctive fear of snakes, so the idea was that I can have a character that has the precision and coldness of a robot, but also inspires a kind of instinctual fear response because it's like a snake, too."

What the Spine Robot lacks in industrial functionality it makes up for in extreme creepiness, unpredictability and impracticality. Each one of its qualities helps create a personality and the personality is how people know it's more than just a machine, it’s a wake-up call from beyond. There was a moment from a recent show. He was using the Spine Robot to pluck dead coyotes from another machine. "I was operating that for most of the show, and I grabbed a coyote and threw it toward the audience," he says. "I saw it land in a puddle and splash this 13-year-old girl, splashed this muddy water all over her. And she just looked horrified at first, then she just started laughing." He imagines her thinking back to that muddy water and that dead coyote in front of her as she herself dies. The 13-year-old on the cusp of adolescence, trying to figure out the world, and a message as comically inscrutable as physics and an airborne coyote, mummified and suddenly splashing down at her feet, the work of some benevolent prankster-artist. What else could she do but laugh?

“You don't want to waste the abilities of the machines,” he says. “That's the first order of business. You want to make sure that you maximize their potential. You want to give them a job to do.” There is well-documented catharsis in violence; you’ve seen it in every movie and Classical painting and Army Reserve recruit wet dream. Where else do you find acceptable outlets for your anti-social impulses? The Juggalo Gathering?

“You don't want to waste the abilities of the machines,” he says. “That's the first order of business. You want to make sure that you maximize their potential. You want to give them a job to do.”

A lot of people interpret his disinterest in audience opinion and hearing capability as a rebellion against the art world. “I don't have a gripe with them, “ he tells me. Then looks down sheepishly, pauses and grins. “Okay. My gripe started when I was in college.” In college, Mark was heavily involved in the local punk scene. He had a professor whose wife ran a gallery in Sarasota. When Mark graduated, she offered to host show for him before he vacated the Floridian shithole. He wanted to deface and mutilate billboards, then take photos of the billboards and put them in her gallery. When he told her that’s what he wanted to do, she offered a curt “Well, Mark, that's illegal. I can't do that.” This non risk-taking disgusted him and, out of spite, he decided he’d invent a whole new art style no one had ever done before. He decided he’d use the art world when he could, but he’d never be beholden to them. “I'm not going to ever have to look back and deal with some art curator going, 'Oh, I discovered Mark Pauline. I'm the one that made him famous'. I was just going to create attention, and go completely outside the art world, unless I chose in my own way to be involved with them.”

One of the reasons he started SRL was to have a system outside the system, and he’s still outside of it today. Most of the art world doesn’t even know who Mark Pauline is and if they do, they can’t decide whether what he does is art. "The art world was much more codified and conservative back then," says Jon Reiss, who shot video of SRL’s early shows. "Mark was kind of anathema to them, whereas someone doing that kind of stuff now would be much more readily embraced. I think SRL broke a lot of ground in that regard. I don't think Mark and the people who worked with SRL have gotten enough credit for that. Part of it is that Mark doesn't give a fuck and hasn't for a long time."

Mark has no training in the mechanics of machine making, he’s been self-taught since he was 17. Living in Florida he’d developed a hobby of exploring old buildings in lush, abandoned areas and read the manuals and books he found there. Before he was of legal age, he got a job where the requirement was knowing how to read blueprints. "I was like, 'Wow, all I have to do is read these books. It just took a couple of days and then I got a job! I'm getting $4 an hour!' And so that kind of got me going on it. So that's how I've always approached mechanical things.”

After college he moved to San Francisco and found lots of abandoned industrial complexes like the ones he explored in Florida. Most of them were complete facilities, rapidly abandoned, harboring technical libraries about all their machinery. Mark went exploring, braving the dogs and barbed wire. He took the books he found home and started reading them. And then he started taking some of the industrial flotsam out of there. In about a week, he came up with the idea that, with all the abandoned machinery and leftover parts, he could do shows with machines and robots. All the parts he needed were there and he knew how to assemble them. He even had a vacated warehouse or twelve at his disposal to build them in. Given the relative ease with which Mark created his own anti-art, pro-carnage universe, it surprises me that no one else is doing this.

You have to be very inspired to take the time out of your life to build these things. It's very hard to do. It's very, very, very labor intensive and very frustrating and very difficult.

“The only way to do what I do would be to directly copy me,” he says. “And there have been people who have tried to do that, but I think that they got very little attention for trying to copy me, because everyone was like, 'Well, that's kind of cool, but it's so much less than SRL.' It's not that interesting to be like something else, especially if there's only a couple of people doing it. And you have to be very inspired to take the time out of your life to build these things. It's very hard to do. It's very, very, very labor intensive and very frustrating and very difficult. Most people won't do that if they aren't getting paid for it. Most people with the skills to do it would just do it as a job and make a nice six-figure salary and call it a day.”

This is not a monetary venture. "I do this stuff cause I like to do it," he says, "not because I think I’m going to make any money at it. I’ve been doing it for 30-some years and I still haven’t made any money at it. So that’s good. That means I’ve succeeded. That measure of success has been achieved."

I wonder if there’s satisfaction, pride or loneliness knowing you’re the only person in the world who does something.

“There's a certain satisfaction in it I guess, not because it's better than what everyone else is doing, but because it's hard to do. It’s so impractical. It's not a realistic thing to do in any way, shape or form. That's what I like about it. I've grown to appreciate things that are like that over the years.”

Witnessing one of Mark’s shows is like a near-death experience, the unexpected and the absolute fear space that it creates but there's so much more beauty in Mark’s work than the violence. But it's bigger than that. It's bigger than that knee-jerk response of being afraid. What it is, is humanitarian.

Mark hates that I bring this up.

“I think that any kind of benefit that comes from these things is incidental. There's nothing practical or intentionally beneficial in any way about any of this stuff. But I think people find beneficial things and people find the practical, positive aspects of them, but that's not what I'm trying to do.”

Back in the lab, Mark kills the Spine Robot and rubs his eyes.

“When I was growing up, I came to appreciate very deeply the fact that there were people out there doing things that moved me. And so I really appreciated people who took the time to create some artifact that I could then participate in, you know? Movies, books, music, whatever. And I always felt like that was the greater purpose in life was to be able to kind of create something that would inspire other people. I'm trying to create an unforgettable and indelible mark in people's imagination.”